Nirad Mohapatra’s requiem to the joint family “Māyā Miriga” has been referred to as the most feted film in the history of Odia cinema that propelled a lesser known regional cinema into national and international recognition at the time it was made. However, since that time both the film and the filmmaker faded away from the landscape of feature films in India. Noted film critic Maithili Rao termed the vanishing of Nirad Mohapatra from the movie making scene after such an ‘exquisitely elegiac, immensely moving first film’ as one of Indian cinema’s greater unanswered questions. Film Heritage Foundation took up the restoration of this forgotten gem as it was in poor condition and we were in danger of losing a precious part of our film heritage.

SHIVENDRA SINGH DUNGARPUR

FILMMAKER, ARCHIVIST AND DIRECTOR, FILM HERITAGE FOUNDATION

Having three world-class restorations to our credit of hidden gems of India’s regional cinema – Aravindan Govindan’s two Malayalam films “Kummatty” and “Thamp̄” and Aribam Syam Sharma’s Manipuri film “Ishanou”, we felt that “Māyā Miriga” was almost an obvious choice – not just for its beauty and the fact that it was in danger of vanishing, but also because it was a very important film from Odisha whose restoration would serve to bring Odia film heritage back into the limelight.

I was aware of “Māyā Miriga” since my days as a film student. P.K. Nair had often spoken about the film in glowing terms and Surender Chawdhary, who taught me when I was a student at the Film & Television Institute of India (FTII) had always believed that it was the best of the New Wave films. Also, I had been very keen to interview the filmmaker Nirad Mohapatra for my documentary “Celluloid Man” as he knew P.K. Nair well and was a great admirer. Unfortunately, I was unable to interview him or meet him before his passing in 2015. “Māyā Miriga” came up another time when I had travelled to Odisha to give a masterclass on film preservation in October 2018 and I was asked when I would restore an Odia film, and “Māyā Miriga” in particular.

Even though “Māyā Miriga” was a film that was out of circulation for a long time, it kept popping up in conversations over the years. As it happened, of the hundreds of films teetering on the verge of disappearing and clamouring to be restored, circumstances dictated that “Māyā Miriga” make the list.

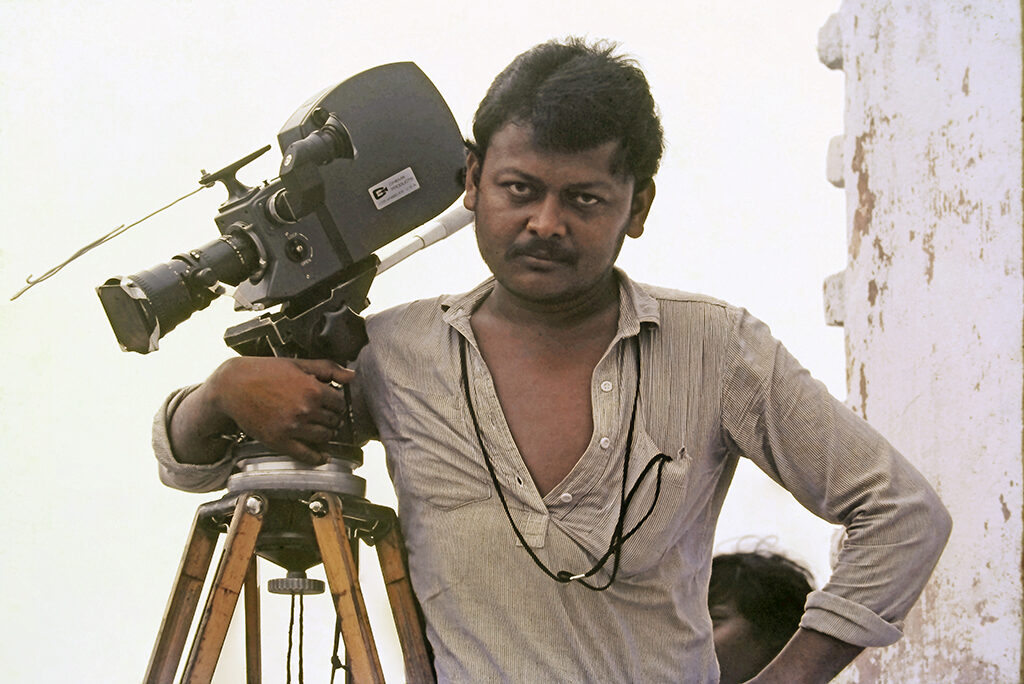

DIRECTOR’S NOTE: NIRAD MOHAPATRA

The making of ‘Māyā Miriga’ was an exciting experience of improvisation within the broad framework of a written story. The film was shot at Puri, a seashore town in Odisha. With a small crew and a team of non-professional artistes, we pitched our tents months in advance to dress up an abandoned house including its courtyard, which was to be our only set. We were lucky to have this house at our disposal and to have the best of both the worlds – a set on location.

I intended the film to be long and compassionate look at its characters, watching the members of a family inexorably progress towards their break-up. I belong there, to the small-town middle class joint family and have been fascinated by its dreams and agonizing nightmares. In it, I see a lot of warmth, fellow-feeling, sharing of experiences and a sense of responsibility. But I also see the tight-rope walking of the married sons, the bitterness of its locked-up daughters-in-law, their need for freedom, economic or otherwise, the maladjustment in marriages and above all, selfishness that can damage its very fibre.

At one level, it is the emotional attachment to the family as against freedom for oneself that provides the mainstay of its conflict. At another, the conflict arises from the social reality of the middle class: its economic status as related to higher education, better jobs and higher positions in the social hierarchy. But ultimately the film is about certain emotional bonds which make up a way of life and the painful realization that they cannot last.

THE RESTORATION PROCESS:

It’s been close to three years since we began on the process to restore Nirad Mohapatra’s film “Māyā Miriga”. It was on November 17, 2020 that I received the first email from Sandeep Mohapatra, introducing himself as the son of the late Nirad Mohapatra saying that he wanted to restore his father’s film and hoping that I could help him. He had been referred to me by Surender Chawdhary, former director of the Film & Television Institute of India (FTII) in Pune, who had also taught me when I was in FTII. I later found out that Sandeep had written to the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) several times regarding his father’s film, but had no response. Finally, Mr. Chawdhary suggested he write to me.

The first step was to locate the original camera negative. Sandeep said he had no idea where it was, but thought that the negative might be in Chennai as the film might have been processed at Prasad Lab there. We reached out to Prasad Lab and finally on January 7, 2021 we found 12 reels of the 16mm original camera negative abandoned in a warehouse as they had been removed from the lab storage for non-payment of dues.

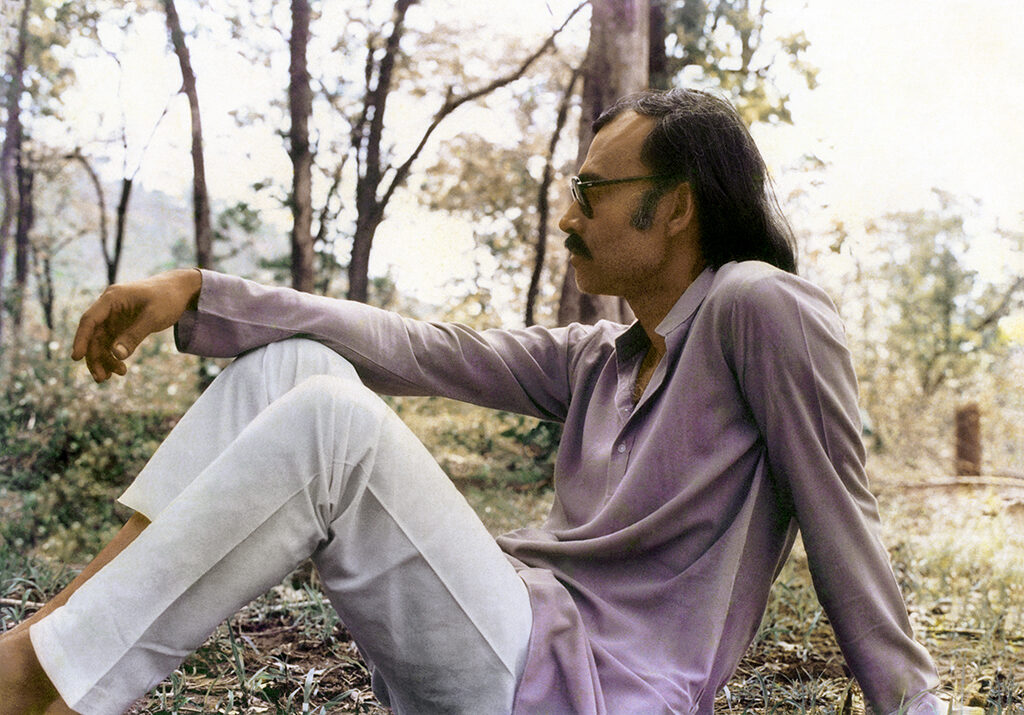

We transported the reels to the Film Heritage Foundation lab in Mumbai and were dismayed to find that the reels had deteriorated badly and were in a very poor condition. The inspection report stated that the reels had strong vinegar syndrome, broken perforations, high shrinkage, mould and halos on the emulsion, strong base distortion and colour fading. Reels 5 and 12 were classified as being in critical condition with the image completely or partially damaged due to plasticizer loss and mould. We knew that the film repair was going to be a daunting task for our conservators and that it would not be possible to scan the negative in India. Our conservators undertook the painstaking manual repair of the film over several months before we could send the negative to L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna for scanning.

When I was In Bologna in 2022, the lab showed me the scan of the negative. As a result of the high level of deterioration of the negative, the scanned material had a number of issues. The image was blurred, had scratches, tears, dust and dirt, frequent and long lasting vertical lines (sometimes very deep green lines) and halos. The situation looked grim.

We were aware that the NFDC-NFAI had two 35 mm prints and we wrote to them to access it. One was a subtitled print and therefore no use to us for the restoration. We decided to scan the 35 mm print at the Prasad Lab in Chennai so that we could use the best scanned portions from both sources for the restoration. The sound was also taken from the 35 mm print. However, the scan of the 35 mm print was disheartening too as due to deterioration the print had colour fading that had turned the colour magenta giving the film a pinkish hue. The faces were blurred and the film was very grainy. Some of the night sequences on the rooftop had turned blue-black where you couldn’t see the faces. Just the grading took nearly two months to get some kind of balance in the colour and sharpness and to control the grain.

RESTORATION CREDITS:

Restored by Film Heritage Foundation at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, with digital restoration done by Digital Film Restore Pvt. Ltd. and scanning at Prasad Corporation Pvt. Ltd.’s Post – Studios in association with the family of the Director, Nirad Mohapatra.

Funding provided by Film Heritage Foundation.

Māyā Miriga was restored using the best surviving elements: the 16 mm original camera negative preserved at Film Heritage Foundation and a 35 mm print preserved at the NFDC-National Film Archive of India.

The restoration was extremely challenging as the original camera negative was found by Film Heritage Foundation abandoned in a warehouse in a very poor condition with certain portions of the film having no image. The 35 mm print had also deteriorated over time. The image was very grainy and blurred in portions and the colours had faded to magenta. The restoration, which took almost three years, needed hours of work on the film repair, digital restoration and colour grading.

SYNOPSIS: MĀYĀ MIRIGA (THE MIRAGE, 1984)

Māyā Miriga is concerned with the gradual and irreversible process of disintegration in a middle-class joint family living in a small town in Orissa.

Raj Kishore Babu, an elderly headmaster of a school, lives modestly in a joint family that comprises his mother, his wife and his five children. Tuku, the eldest son, who is quiet and dutiful, works as a lecturer. Prabha, Tuku’s wife, is expecting their first child and is dedicated to the running of the household.Tutu, the second son, is the great hope of the family. Following his brilliant academic career in Delhi, he is assured a prestigious government job. The third son, Bulu, clings to the family for his emotional security and is quick to see himself as a failure despite Tutu’s encouragement. The fourth son, Tulu, is the defiant one, ready to challenge the established family norms. Tikina, the youngest child, is still at school. The family’s emotional centre is the gentle and wise grandmother. It is, however, Raj Kishore Babu who lays down the rules.When Prabha gives birth to a daughter, family expectations are let down. But soon enough, Tutu’s final selection for the prestigious job more than makes up for everything. As his newly acquired status demands, he marries above his social milieu.

The couple returns to Tutu’s home with many gifts given as dowry. The house is transformed with modern gadgets and new furniture. Irritations arise, which reflect the beginning of changes in the joint family household. Tutu’s city-bred wife will not follow in Prabha’s footsteps as a traditional daughter-in-law, the role that is expected of her. On the flimsy pretext of her mother’s sickness, she declines to stay with her in-laws while her husband is away. Prabha resents the preferential treatment given to the new couple. Soon after the couple leave, the grandmother suffers a stroke while performing puja, and dies the same night. Prabha’s sense of oppression, resulting from the joint family system, increases. She sees others who are better off because they do not need to share their income. Prabha can only express her resentment gradually to her husband, Tuku, as she realizes the deep dedication he feels towards the family.

Raj Kishore Babu retires from his work as headmaster. He is depressed and only finds solace in the company of another retired official. The latter pins all his hopes on the return of his son who lives in America.Tulu, the defiant one, now has a first class B. A. degree. He wishes to follow his brother’s example and be sent to study in Delhi. Bulu, the ‘failure’ of the family, realizes that he will now be left completely on his own. The family persuades Tulu to await the return of the successful brother Tutu, who visits on the way to his first posting. His wife accompanies him only to collect her ‘dowry’ possessions despite her husband’s awkwardness at her material preoccupations.

When Tutu is required to help finance Tulu’s education in Delhi he is reluctant. The father denounces the favourite son and makes him aware of the sacrifices they underwent in order to educate him. Finally, Tutu, in shame, gives in. The eldest son chooses this moment to slip in the news that he has been deputed to a post in the state capital, and will be leaving town shortly.

The disintegration of the family’s unity is by now apparent. An uneasy silence follows. In the quietness of the night, and in the privacy of their rooms, the family members recollect the warmth of their togetherness, yet are painfully aware of the impossibility of staying together. Next morning, Tutu and his wife leave with their ‘dowry’. Prabha, for the first time, refuses to light the coal oven. The mother must now cook for the family. Reflecting on the state of affairs, Raj Kishore Babu ironically asks his two-year-old grandchild: “Will you too leave us?”

CAST AND CREW DETAILS:

Māyā Miriga (The Mirage), India, 1984, Nirad Mohapatra

110 mins, Colour, Odia, English Subtitles, Aspect Ratio 1.37:1

Script and Direction: Nirad Mohapatra, Story: Nirad Mohapatra and Bibhuti Patnaik, Cinematographer: Rajgopal Mishra, Editor: Bibekananda Satpathy, Sound: R. Shrinath, Music: Bhaskar Chandavarkar, Producer: Lotus Film International

Cast: Bansidhar Satpathy, Manimala, Kishori Debi, Binod Mishra, Manaswini Mangaraj, Sampad Mohapatra, Sujata Mohapatra, Bibekananda Satpathy, Shriranjan Mohanty, Tikina

FILM REPAIR STILLS:

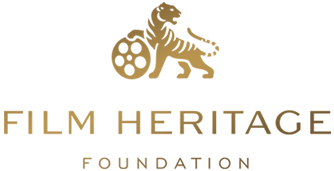

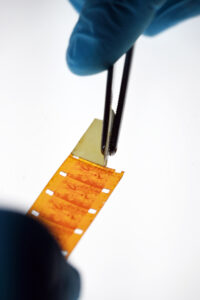

ABOUT NIRAD MOHAPATRA:

Nirad Mohapatra was born on November 12, 1947 in Bhadrak, Odisha. He was the eldest of 7 siblings. His father was a freedom fighter (in pre-independence India), journalist and later entered politics in independent India. His mother was a teacher in school. The foundation to Nirad’s value system was laid with this background. He was also exposed to rural and urban life while growing up. All this made him very aware of the realities of middle class life. His interest in cinema was kindled from his childhood days and further strengthened by the cinema very near his house in Bhadrak, Orissa.

He obtained a B.A. degree with distinction in 1967 and then enrolled for a postgraduate degree in Utkal University. He discontinued his course at Utkal University and joined the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune from where he graduated with a diploma in film direction in 1971 and joined the Institute as a lecturer in 1972. In 1974 he founded Cinexstasy, a film society in Bhubhaneshwar, Odisha, screening classics of world cinema accompanied by analysis. He ran the society until 1983. He edited the film section of arts journal Mana Phasal, continued to lecture at FTII, wrote for national journals, made documentary films and taught a film appreciation course at Utkal University.

In 1984, he made “Māyā Miriga”, his first and only feature film, considered to be a classic milestone in the history of Indian cinema in general and Odia cinema in particular. The film was critically acclaimed and went on to win many accolades. It placed second in that year’s Indian Panorama awards for Best National Film and was selected for the Critics’ Week at the Cannes Film Festival. It was adjudged the Best Third World Film at the International Film Festival Mannheim-Heidelberg. It received a special jury award at the Hawaii International Film Festival and was screened at Locarno, BFI London Film Festival and the Los Angeles Film Festival.

Nirad Mahapatra passed away on February 19, 2015.

MĀYĀ MIRIGA: BEFORE AND AFTER RESTORATION

WORLD PREMIERE AT IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2024 ON JUNE 27, 2024:

NEWS ARTICLES:

(Click on image to read the full article)